I’m reading Israel Finkelstein’s The Forgotton Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (Open Access!), and really enjoying it. My impression is that Finkelstein often gets painted as this arch-minimalist with nothing but complete distrust for the Hebrew Bible as a historical source (as in passing in this very-viral-among-very-select-demographics hit from a decade ago). But so far, I think he gives the biblical evidence a fair hearing and does a convincing job of integrating it with epigraphic sources and, his specialty, archeology.

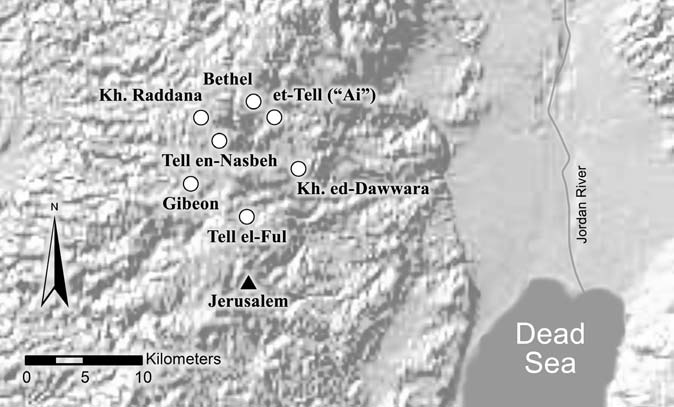

For instance, Finkelstein accepts the biblical claim that Israel first became a monarchy under King Saul, a Benjaminite (ch. 2 of the book). There’s a number of fortified sites from the right archeological period right smack in the territory of Benjamin, between Jerusalem (which was pretty insignificant at this time) and Bethel.

Jerusalem.” Figure 10 from Finkelstein (2013)

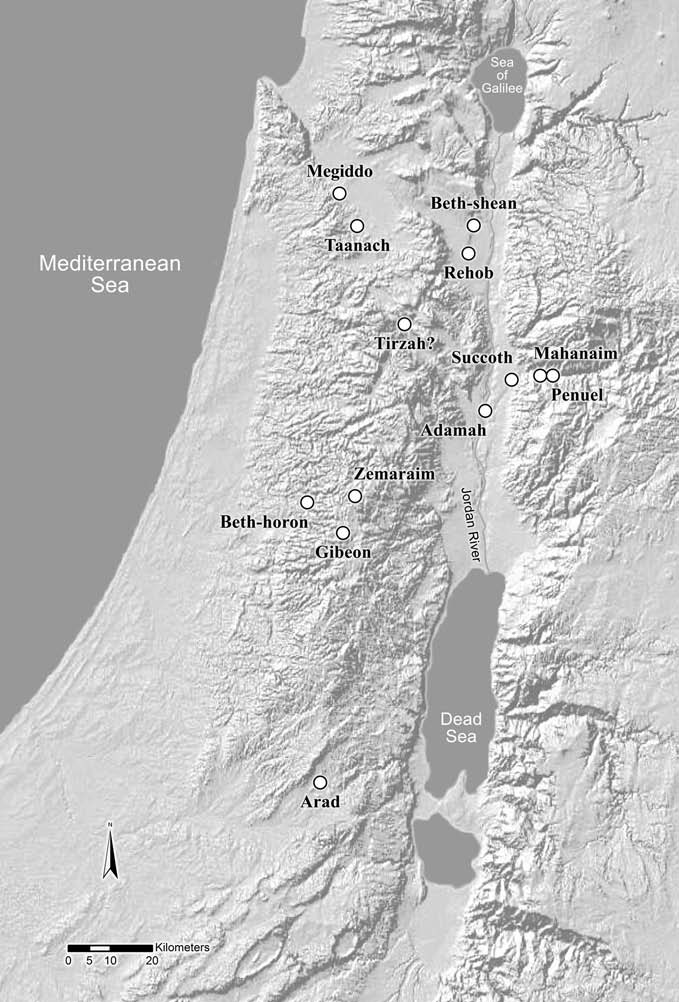

Finkelstein connects this with an argument from the Palestinian campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I. Here, he deviates from the biblical account, which dates this campaign to the reign of Jeroboam I, not Saul or his direct successors; but that could be anti-Jeroboam propaganda, par for the course in 1 and 2 Kings. Fair enough.

Shoshenq campaigned against some important cities in the fertile northern valleys, but interestingly also against 1) some cities in Benjamin, 2) some cities along the Jabbok in Transjordan, and 3) practically nothing in Judah.

temple of Amun at Karnak, Upper Egypt.” Figure 12 from Finkelstein (2013)

This is interesting, because:

Both the Sheshonq I list and the biblical sources describing the Saulide territorial entity speak about the same geographical niche in the hill country, north of Jerusalem, and both link it with the Jabbok River area; the biblical story specifically connects the Gibeon region with Jabesh-gilead (1 Sam 11; 2 Sam 2:4–7) and Mahanaim (2 Sam 2:12). As I have emphasized above, this geographical combination—of two relatively remote and off-the-beaten-track areas—is unique, and viewing their grouping as a mere coincidence (especially that the two sources seem to describe events that could have been not-too-remote chronologically) seems to me highly unlikely.

(Finkelstein 2013: 47)

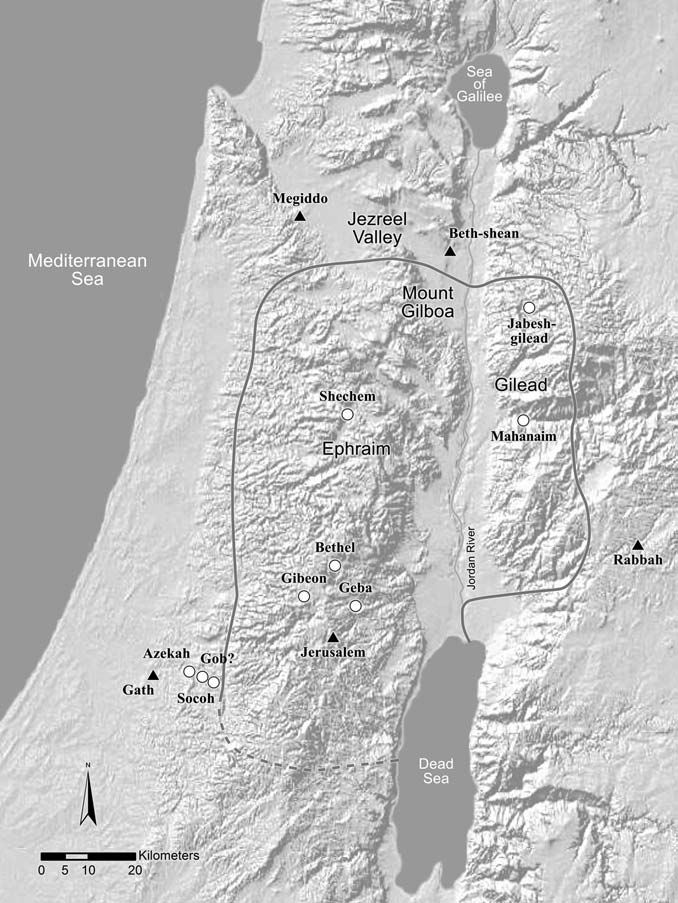

Together with some other data like the tradition about Saul and his son Jonathan being killed in battle with the Philistines on Mount Gilboa, really far away from where we expect any Philistines, this leads Finkelstein to a reconstruction along the following lines:

- Saul and his dynasty ruled “over Gilead and the Ashurites and [the edge of] Jezreel and Ephraim and Benjamin [i.e.] all Israel” (2 Sam 2:9), see the map below.

- By projecting power into the Valley of Jezreel in the north and the coastal plain in the southwest, this threatened Egyptian interests.

- Under Shoshenq, Egypt came and put an end to this.1 The memory of the Egyptians as Saul’s enemy faded, leaving only that of their allies or auxiliaries, the Philistines.

Two thoughts on this:

- In Chapter 1, Finkelstein notes that a number of big cities in the lowlands show a kind of Canaanite revival at the same time the Israelites appear in the highlands (Finkelstein calls this period New Canaan). Then they get destroyed around the time Israel becomes a monarchy, possibly by raids directed by the Saulides or other early northern Israelite kings. If it was the house of Saul, I think that provides some new insight into the meaning of Gen 49:27, the most warlike of the tribal sayings known as the Blessings of Jacob: “Benjamin is a rending wolf: in the morning he devours prey, in the evening he divides plunder.”

- A surprising number of these sites with connections to the house of Saul are mentioned in stories about Jacob, specifically as being named by him: Bethel, Mahanaim, Penuel, and Succoth. Two more, Gilead and Mizpah, are also close to the Jabbok. Are these traditions from the time of Saul and his earliest successors? If so, it’s a bit odd that Saul’s capital of Gibeah isn’t mentioned in connection with Jacob.2 Still, it does make sense for some founding legends about Israel to date back to the time the kingdom of Israel was actually founded…

On to Tirzah and Jeroboam I. More thoughts to follow, no doubt.

Leave a comment